“You may leave the land, but the land never leaves you.”

I’d like to tell you a story. A true story. The story a man who leaves behind his homeland.

His wife and children then follow. A family of four: mother, father and two daughters.

Setting up home in Leicestershire in the UK, he never returns to his homeland, bar one brief visit to sort paperwork.

His wife? She never steps foot on home soil again.

A new country, new name (albeit not legally), he dons a new identity. His homeland is now a memory now to be forgotten, the remnant of an old life some 2,300km away.

A new language, a new home, a new start. What is he seeking you might ask? Or perhaps fleeing?

What is he longing for? And what has he left behind, desperate to forget?

Any guesses? Well, yours are as good as mine.

Poverty? Likely yes. New opportunities? Very much so.

Yet I also sense that there’s more to it than that. More to this story for sure.

What I do know is that this is the story of my late grandfather: Silvio De Blasio. An Italian born man, he became known as “Joe”:

“I’m not Silvio, I’m Joe now”

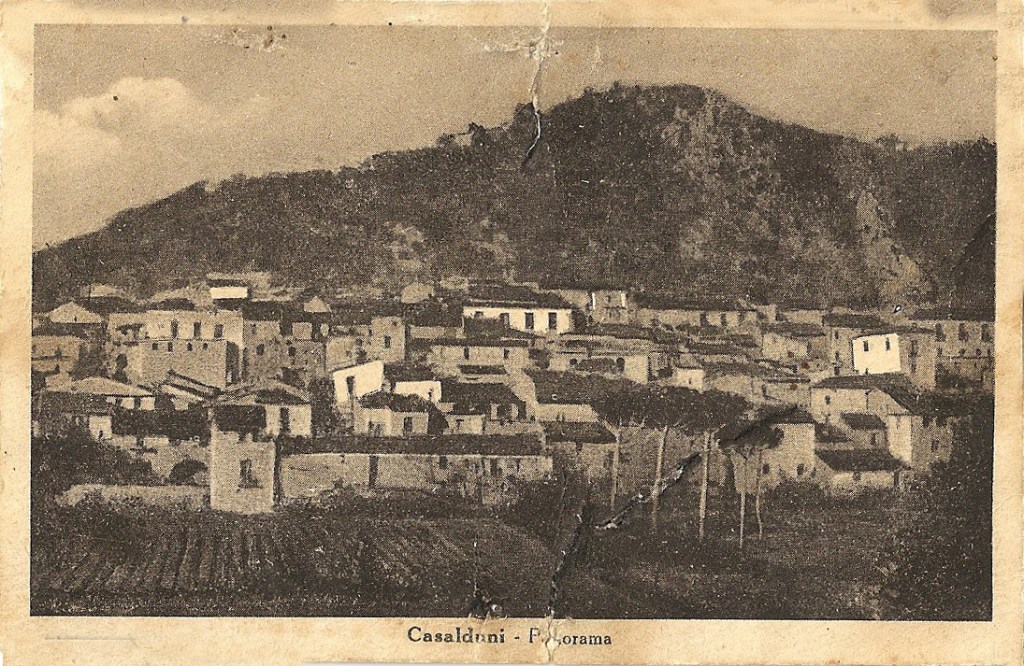

This was apparently the testimony of my late grandfather after moving to the UK from the small town of Casalduni in Campania after World War II.

The date? I’ve yet to find out. Likely sometime between 1950 and 1970. That’s all I know on the specifics.

However, what I have discovered through research and conversations with Italian family is that this was a journey that represented not only building a new home, but leaving the old one behind – a journey of loss, likely pain and also shame.

I can’t and won’t judge my late grandfather. He’s not here to shed light on the many, many questions I have.

The world then was a very different place. Post-war Italy was in ruin: economically and politically. A former prisoner of war captured by the British (my grandfather was not a fascist), he decided to return to the UK – this time by choice.

I don’t know the date he arrived, neither my mother.

As a child, many things remained a mystery. I retained a few snippets of information that were recalled to me by my mother. But many a question was met with silence – including her arrival to the UK.

Growing up in a monolingual household (English), I was the remainder of a family of two generations where Italian culture and identity had been eroded.

Having started Italian classes at secondary school (which would reach postgraduate level), my mother decided it was time to take me to Italy for the first time as my two grandparents were no longer alive.

It was time to go back to our roots. Yet these roots were buried deep.

Greeted in Italian by an aunt, I embarrassingly explained that I couldn’t (really) speak Italian (yet).

No one had taught me. My aunt hadn’t. And my mother seemingly couldn’t. An hour or two of beginners Italian in Year 9 (in my early teens) was a very late starting point.

Many a year later, having visited the country for myself several times, studied at an Italian university for an ERASMUS year, and thankfully having grasped the language fairly fluently, I’m trying my best to find answers. To unearth those roots, for my mother, my grandparents and for myself.

Travelling to Milan a few weeks ago, seeing my cousin and her family, I asked question after question. With my cousin penning down our family tree and a phone call later to her mother, I got some insight – but no concrete answers.

“She would have spoken Italian” was the unanimous view.

Pondering over how old my mother was when she left Italy, we’ve don’t have concrete answers (yet!).

One thing for sure though is that my grandmother couldn’t speak English. Therefore, my mother must have communicated with her mum in Italian.

However, the only time I heard her native tongue in full flow was during one angry outburst at a terrible “Italian” restaurant in Paris in the early 2000s on a family holiday. It was as though buried deep inside her memory, pushed to be forgotten, the rage unlocked her native language.

Fast, fluent: it was clearly her native tongue. A tongue she’d either wanted or had been forced to forget, to bury deep. Yet one that I refuse to.

A few months before my recent trip to Milan, I uncovered my mother’s Italian passport and a childhood photo. Many an internet research and a DNA kit later, I’m still looking for answers.

What I have learnt however is this: this wasn’t an uncommon experience. To forget, to leave it all behind, to focus on the now.

Assimilation was the policy of choice in the UK at the time. And so, my family lived in an era with negative stereotypes abound, outdated policies and a lack of appreciation, understanding and tolerance towards other cultures and backgrounds.

Pluralism was yet a distant speck in the fabric of British society. My family likely did what they had to do to survive.

Survival mode teaches us to forget, to push aside, to bury deep – to carry on with the day-to-day, the now, the essential. But it’s not healthy.

Intergenerational trauma, dissociative amnesia, linguistic trauma (forgetting one’s native language) – they all cause us to supress, to shame, to forget and deny, not to embrace, cherish and nurture.

I don’t know what pain they may have left behind or faced when they arrived. But, I sense there’s more to it than I understood as a child – likely the effects of racism, trauma and (self-)suppression.

As a society, we don’t recognise enough the hardship, struggle and strength it takes to try and build a new life far from home.

To move to another country, to leave everything behind takes incredible courage.

It’s challenging, it’s difficult and it affects everyone differently in terms of navigating one’s identity.

Britain wasn’t the place it is today. Far from perfect today, it’s a long way off what is once was.

I haven’t walked in my grandfather’s shoes. For whilst I’ve had my own journeys overseas, they’ve been in different places, at different times, in different contexts.

So, as I come to realise that I may never fully get my answers, what I do know is this: I have nothing but love and gratitude for my late grandfather. And I don’t judge him.

I have nothing but respect and admiration for anyone who choses to or is forced to leave their home behind: whether migrant, refugee or asylum seeker.

As for my grandfather, I honour his courage, his dedication and his will to integrate into British society.

I understand he did his best, that times were different and that challenges were likely vast.

And I also honour my ancestry, my mother’s homeland and my heritage. That’s why I’m reclaiming it.

I don’t need to choose. I’m British, born and bred. I always will be. I’m also Italian. Just like my mother, my grandparents and their parents before them.

Italy wasn’t a land grandad Joe seemingly wanted to remember. Who knows.

But it’s a land that I do – and I’m trying my very best to make it (my second) home.

Ti voglio bene, nonno Silvio. Tanto.

Dedication

This blog is dedicated to my late mother and grandparents. May you rest in peace. Vi voglio tanto bene.

Featured images: my late grandparents Genoveffa and Silvio (“Jenny and Joe”) in Loughborough, UK (left) and my late mother Emilia (right) (photo believed to have been taken in Italy, date unknown).